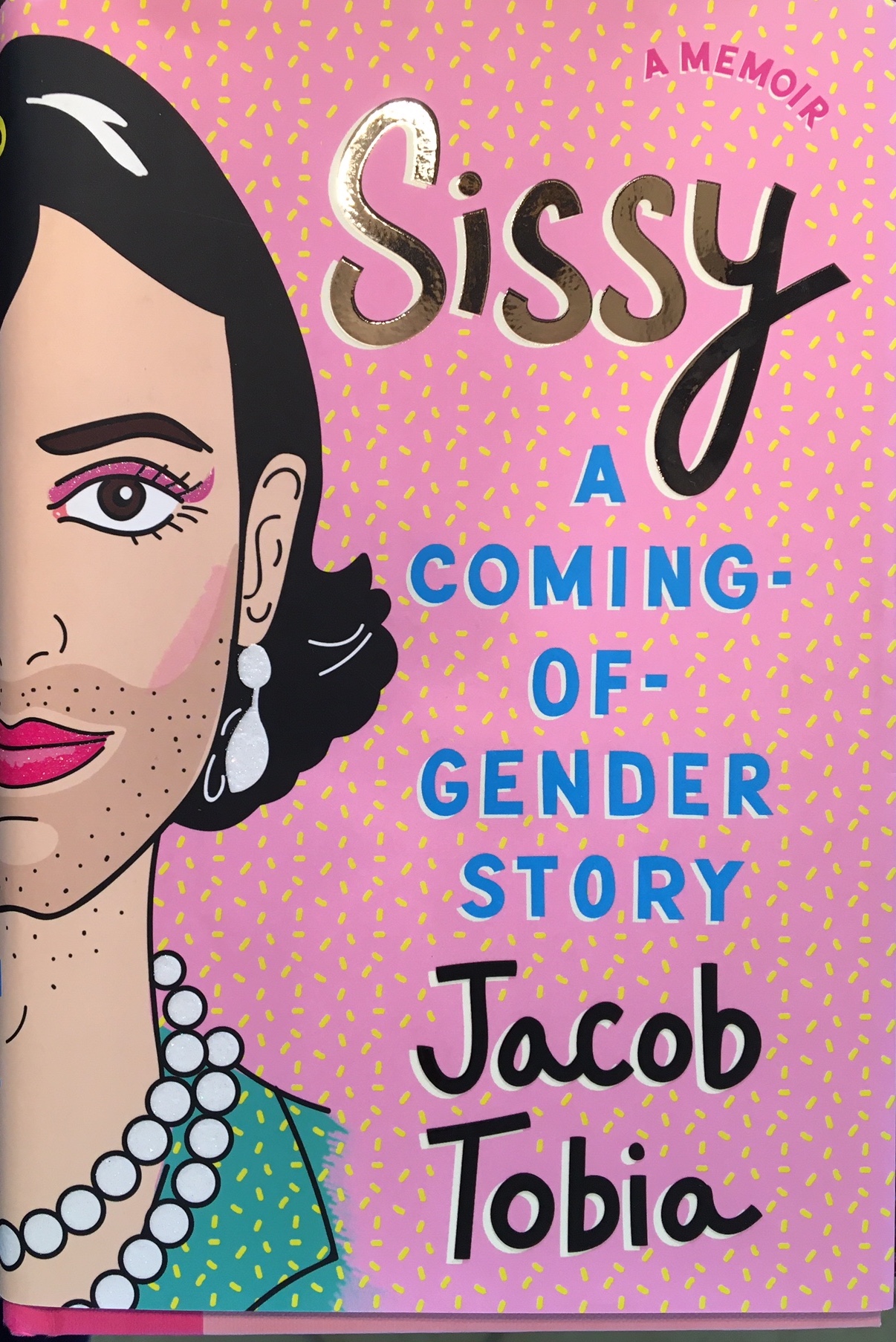

“I was taller and shinier than the Rockefeller Center Christmas tree.” That’s what Jacob Tobia writes after describing their successful fundraising efforts for an LGBTQ homeless youth center in their recent book Sissy,” which they describe as a “heart-wrenching, eye-opening, and giggle-inducing memoir about what it’s like to grow up not sure if you’re (a) a girl, (b) a boy, (c) something in between, or (d) all of the above.”

“I was taller and shinier than the Rockefeller Center Christmas tree.” That’s what Jacob Tobia writes after describing their successful fundraising efforts for an LGBTQ homeless youth center in their recent book Sissy,” which they describe as a “heart-wrenching, eye-opening, and giggle-inducing memoir about what it’s like to grow up not sure if you’re (a) a girl, (b) a boy, (c) something in between, or (d) all of the above.”

It was the first time in their coming-of-gender story in which their joyfulness at their self-discovery truly came through. In Sissy, Jacob describes what it was like for them growing up surrounded by people who not only didn’t accept them, but who also didn’t understand. None of the labels people had learned were applicable.

My son Jeremy’s journey brought him from childhood, where the label “tomboy” didn’t capture his true gender identity, through his decision to have top surgery, change his name and pronoun usage, take hormones to go through male puberty, change in legal status, and finally, become an advocate. It took him a few years longer than it took Jacob, but I couldn’t help but see the similarities.

And the differences. So many differences. Jeremy was identified as female at birth, but eventually figured out that he is a man. I’ve written previously about my initial reaction of not believing that being transgender is a real thing, through recognizing that the child I love is the same person, regardless of his gender identity, to becoming an advocate for the transgender community. As part of that, I worked conscientiously to use the right pronouns, to refer to my son as “he” and to call him by his new name.

I was pleased that this change came easily to me. With the exception of difficulties when I go into storytelling mode about Jeremy as a child, I rarely slip up. But no sooner had I become accustomed to using respectful terminology for binary people like my son (i.e., those who consider themselves to be either male or female) when I started to meet people like Jacob, individuals who are non-binary, who’s inner sense of gender is neither strictly male or female, but somewhere on the spectrum between the two, or, as Jacob says, “all of the above.”

The book Sissy welcomes me into the world of the gender nonbinary and nonconforming. Through sharing their story, Jacob becomes a real person to me, with feelings, a history (or as they might say, a “herstory”), with successes and failures, with self-understanding and a growing sense of understanding the world around them. The writing is at its best when Jacob relates anecdotes to illustrate their points. Their decision to wear high heels and then write about it for a college admissions essay. Getting harassed while a student at Duke and feeling chagrined that they didn’t do more to fight the bullying. The reaction of their mom about going to church presenting as their true self.

It is when Jacob shares these vignettes that the reader sees them as a complete person. That’s when I found myself choked up and wanting to give them a hug and congratulate them on what they’ve accomplished.

Sissy is a must-read for those who want to extend their understanding of the transgender community to include the nonconforming. And for nonconforming youth who rarely get to see themselves in literature because characters like them are rare, this book will envelop them with a sense of acceptance.

Your family’s story has been a real gift to me to help me understand my grandchild who, during her senior year of high school, expressed her belief that she has gender dysphoria. The depth of this is a lot to get my mind around, and you have enabled me to stop dwelling on possible parenting inadequacies, grieving over the loss of my granddaughter, etc., and instead finding my heart open to feeling nothing but compassion for her-now-him and his parents. I thank you from the bottom of my heart for this clarity!